The impact on John Ball School

The importance of daylight: a key educational resource

The school currently benefits from south-facing classrooms and a playground with uninterrupted, full-spectrum daylight. The proposed development would permanently change this, affecting many windows, including classrooms, at the school.

Although bright days can be managed with blinds, as is currently the case, a structural loss of daylight, especially on overcast days when classrooms depend on every bit of natural light they can get, cannot.

Extensive research shows that natural light is one of the strongest environmental predictors of children’s learning, attention, wellbeing, and academic progress. Large-scale studies (Baloch 2021; Heschong 2002; Kuller & Lindsten 1992 and many more) consistently demonstrate that better daylight leads to significantly higher pupil performance and improved mood, focus and cognitive development. It is a key educational resource and one that should be strongly protected.

For reference, we have included in Appendix 1 below a list of useful links and brief summaries of the key findings from these studies.

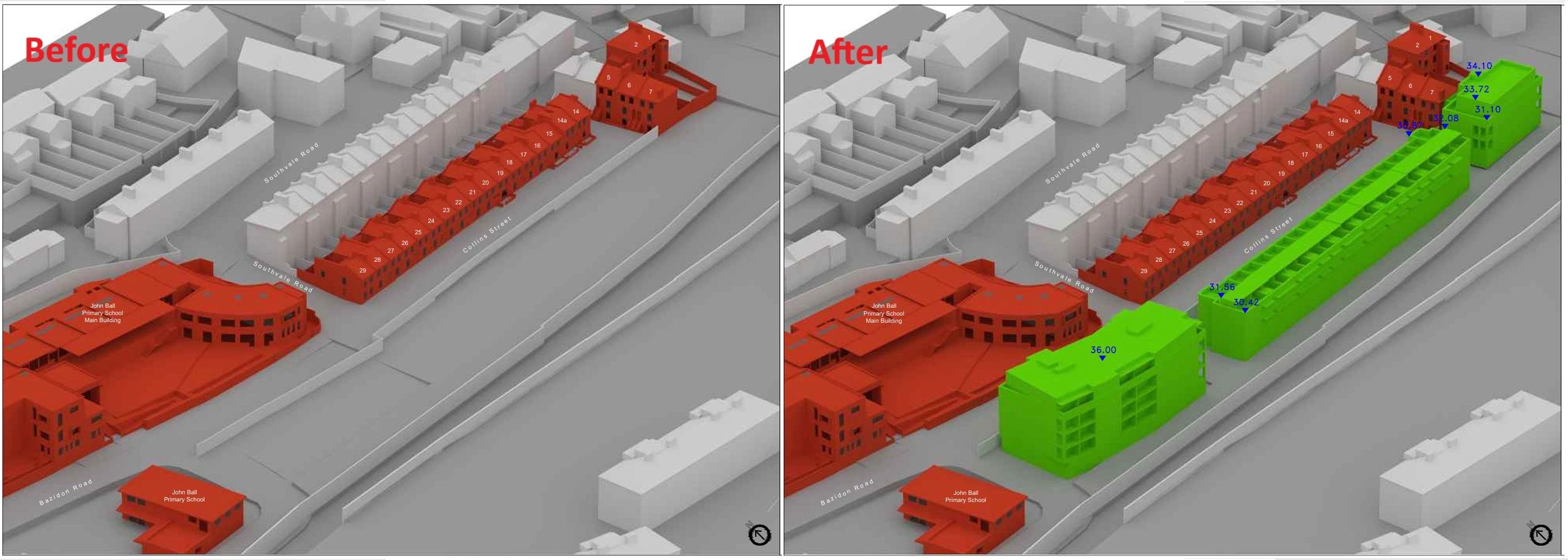

Image created using AI

The school will suffer a light injury

The developer’s light report claims the school would not be significantly affected. Our independently commissioned, crowdfunded study from Rapleys found the complete opposite: numerous windows fail VSC and daylight distribution tests, and Rapleys describe the developer’s conclusion as “simply not true”.

The impact is severe enough that the Right of Light specialists we are in contact with believe that there may be grounds for a claim, as is certainly the case with many of the properties on Collins Street.

Image created using AI

Overlooking, privacy and views

The importance of outlook and privacy

Pupils at the school currently enjoy a private, sheltered environment which is screened by ivy and trees. The classrooms and playground look out through trees across an open space towards the railway. Under this proposal, they would instead face a five-storey block at very close proximity, with 39 windows directly overlooking the playground and surrounding classrooms.

Research shows that natural views reduce stress and support focus and wellbeing (Lindemann Matthies 2021; Pearson 2023; Tanner 2009 and others). Replacing open views with a close, imposing building removes these benefits. We have included in Appendix 2 a selection of these studies.

Primary-aged children also need to feel unobserved to play freely; overlooking at this proximity in a school setting is incompatible with the need to safeguard pupils, particularly as the school would have no control over who is watching. Similar concerns have been raised elsewhere; for example, in Skipton, a primary school formally objected to a residential development overlooking its playground, citing risks to the children’s safety and wellbeing.

The separation distance makes the situation even worse

Lewisham has traditionally applied an 18-21m separation distance to protect privacy between facing windows. Although no longer in the 2025 Local Plan, councillors have as late as October 2025 reaffirmed its relevance in a strategic planning committee meeting. Block C would, we believe, fall below this threshold.

It is also important to note that this guideline was designed for adult residential settings, where occupants can simply step back from a window if they feel overlooked.

A primary school is far more sensitive environment and children playing in the playground or working in classrooms cannot ‘move away’ from views into these spaces. The safeguarding and wellbeing implications are therefore significantly greater than in a typical residential context.

Image created using AI

Construction Noise and Disruption

The impact of environmental noise on learning

The World Health Organisation recognises noise to be among the top environmental risks to health and a cause of cognitive impairment in children.

Construction would take place over an extended period in extremely close proximity to classrooms and the playground, especially those of the youngest children at John Ball - nursery, reception and KS1. The construction will involve continuous drilling, piling, excavation and heavy vehicle movements over a period of what we believe to be at least 3 years, possibly longer.

There is a significant body of evidence which shows that chronic environmental noise slows cognitive development, reduces memory, impairs reading and verbal comprehension, increases stress and fatigue, and exacerbates existing mental health and SEN challenges (Erickson and Newman 2017; Evans 1998; Shield & Dockrell 2006; Stansfield 2012, and others).

This noise and associated vibration caused by the construction work would create a degraded and and potentially harmful learning environment for a substantial part of our children's time at John Ball.

We have included a selection of these studies in Appendix 3.

Image above and right created using AI

Cumulative Harm

While each issue alone is significant, together they produce a cumulative environmental burden: loss of daylight, loss of natural views, increased overlooking, reduced privacy, and years of noise.

Taken together, these effects would materially and, with the exception of construction noise, permanently, degrade the learning environment and pupil wellbeing at John Ball.

Appendix 1 - Daylight Studies

Baloch, et al, "Daylight and School Performance in European Schoolchildren," International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021, 18, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010258

This population-based SINPHONIE (Schools Indoor Pollution and Heath: Observatory Network in Europe) study provides information on relationships between lighting conditions and school performance for 2670 elementary schoolchildren, aged 8–13 years from 155 classrooms in 53 schools across 12 European countries; it found that classroom characteristics associated with daylighting significantly impact the performance of the schoolchildren and may account for more than 20% of the variation between performance test scores.

Lisa Heschong, Roger L. Wright, and Stacia Okura, “Daylighting Impacts on Human Performance in School,” Journal of the Illuminating Engineering Society, Vol. 31, No. 2, Jul 2002, 101-114, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00994480.2002.10748396

This study of over 2000 US primary classrooms in three geographically diverse precincts established “a statistically compelling connection between daylight in classrooms and student performance,” finding that natural light positively contributes to a higher academic performance. Classrooms with the highest daylighting saw 20-26% faster progression in Maths and English compared to those with the least daylight.

Rikard Küller, Carin Lindsten, “Health and behavior of children in classrooms with and without windows,” Journal of Environmental Psychology, Volume 12, Issue 4, December 1992, 305-317.

This study compares the level of daylight across four education settings and verifies the importance of daylight for the regulation of growth and stress hormones in school children.

Baraa J. Alkhatatbeh, et al. “Multi-objective optimization of classrooms’ daylight performance and energy use in U.S. Climate Zones,” Energy and Buildings, Volume 297, 15 October 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113468

The literature review in the introduction to this study on optimising daylight provision in US schools provides summary references to numerous other studies that evidence the importance of daylight in educational settings.

Appendix 2 - Window View Studies

C. Kenneth Tanner, (2009),"Effects of school design on student outcomes", Journal of Educational Administration, 2009, Vol. 47 Issues 3, 381 – 399.

As well as verifying the importance of daylight in academic performance, especially in Science and Reading vocabulary, this study found that “views significantly influenced the variance of Reading vocabulary, Language arts, and Mathematics.”

Amber L. Pearson, et al., “Elementary Classroom Views of Nature Are Associated with Lower Child Externalizing Behavior Problems,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2023, 20, 5653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095653

This study of primary school children in Michigan found that higher levels of visible nature, particularly trees, from classroom windows were associated with lower externalizing behaviour problems scores, further suggesting that “classroom-based exposure to visible nature, particularly trees, could benefit children’s mental health, with implications for landscape and school design.”

Lindemann-Matthies, et al., “Associations between the naturalness of window and interior classroom views, subjective well-being of primary school children and their performance in an attention and concentration test,” Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 214, October 2021

This study of 634 children between the ages of 8-11 at primary schools in Germany found a positive correlation between the naturalness of window views (ie trees rather than the built environment) and children’s well-being, including less stress feelings and greater concentration.

Li, et al., “Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue,” Landscape and Urban Planning 148 (2016) 149–158.

This study of high school students in the US demonstrates that classroom views to greenery rather than built environments result in a restorative effect from external stress and better performance on attention tests.

Appendix 3 - Environmental Noise Studies

Erickson and Newman, “Influences of Background Noise on Infants and Children,” Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2017, Vol. 26(5) 451457.

This literature review provides a survey of numerous studies that address the many detrimental effects of noise on the developing brains of very young children, particularly the impairment of speech comprehension and language learning.

Dockrell and Shield, “Acoustical Barriers in Classrooms: The Impact of Noise on Performance in the Classroom,” British Educational Research Journal, June, 2006, Vol. 32, No. 3, 509-525.

This study of UK schoolchildren, including those with SEN and English as a second language, found that environmental noise has significant negative impact on non-verbal information processing tasks.

Stansfeld et al., “Noise,” in The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology, ed. Susan D Clayton, Oxford University Press, 2012, 375-390.

https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199733026.013.0020

This chapter reviews the negative cognitive and health outcomes of environmental noise generally and on children, citing academic performance and behaviour. It has been observed that children with existing mental health and SEN challenges are particularly vulnerable to these adverse effects.

Evans et al., “Chronic Noise Exposure and Physiological Response: A Prospective Study of Children Living under Environmental Stress,” Psychological Science, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Jan., 1998), 75-77.

This study, based on aircraft noise, found that chronic exposure to noise elevated psychophysiological stress (resting blood pressure and overnight epinephrine and

norepinephrine) and depressed quality-of-life indicators over a 2-year period among 9- to 11 -year-old children. See also Evans, et al., “A Prospective Study of Some Effects of Aircraft Noise on Cognitive Performance in Schoolchildren,” Psychological Science, Sep., 2002, Vol. 13, No. 5 (Sep., 2002), 469-474, for a discussion of evidence from the same study demonstrating an impairment to long-term memory and reading ability from chronic noise exposure.